| Network Working Group | D. Crocker |

| Internet Draft | Brandenburg InternetWorking |

| <draft-crocker-email-arch-11> | October 31, 2008 |

| Intended status: Standards Track | |

| Expires: April 2009 |

Internet Mail Architecture

draft-crocker-email-arch-11

By submitting this Internet-Draft, each author represents that any applicable patent or other IPR claims of which he or she is aware have been or will be disclosed, and any of which he or she becomes aware will be disclosed, in accordance with Section 6 of BCP 79.

Internet-Drafts are working documents of the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF), its areas, and its working groups. Note that other groups may also distribute working documents as Internet-Drafts.

Internet-Drafts are draft documents valid for a maximum of six months and may be updated, replaced, or obsoleted by other documents at any time. It is inappropriate to use Internet-Drafts as reference material or to cite them other than as “work in progress”.

The list of current Internet-Drafts can be accessed at <http://www.ietf.org/ietf/1id-abstracts.txt>.

The list of Internet-Draft Shadow Directories can be accessed at <http://www.ietf.org/shadow.html>.

This Internet-Draft will expire in April 2009.

Over its thirty-five year history, Internet Mail has changed significantly in scale and complexity, as it has become a global infrastructure service. These changes have been evolutionary, rather than revolutionary, reflecting a strong desire to preserve both its installed base and its usefulness. To collaborate productively on this large and complex system, all participants must work from a common view of it and use a common language to describe its components and the interactions among them. But the many differences in perspective currently make it difficult to know exactly what another participant means. To serve as the necessary common frame of reference, this document describes the enhanced Internet Mail architecture, reflecting the current service.

Over its thirty-five year history, Internet Mail has changed significantly in scale and complexity, as it has become a global infrastructure service. These changes have been evolutionary, rather than revolutionary, reflecting a strong desire to preserve both its installed base and its usefulness. Today, Internet Mail is distinguished by many independent operators, many different components for providing service to users, as well as many different components that transfer messages.

Public collaboration on technical, operations, and policy activities of email, including those that respond to the challenges of email abuse, has brought a much wider range of participants into the technical community. To collaborate productively on this large and complex system, all participants must work from a common view of it and use a common language to describe its components and the interactions among them. But the many differences in perspective currently make it difficult to know exactly what another participant means.

It is the need to resolve these differences that motivates this document, which describes the realities of the current system. Internet Mail is the subject of ongoing technical, operations, and policy work, and the discussions often are hindered by different models of email service design and different meanings for the same terms.

To serve as the necessary common frame of reference, this document describes the enhanced Internet Mail architecture, reflecting the current service. The document focuses on:

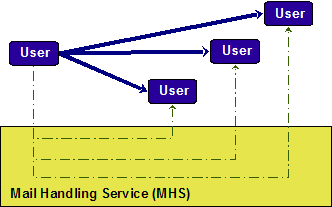

The first standardized architecture for networked email specified a simple split between the user world, in the form of Mail User Agents (MUA), and the transfer world, in the form of the Mail Handling Service (MHS), which is composed of Mail Transfer Agents (MTA). The MHS accepts a message from one User and delivers it to one or more other users, creating a virtual MUA-to-MUA exchange environment.

As shown in Figure 1, this defines two logical layers of interoperability. One is directly between Users. The other is among the components along the transfer path. In addition, there is interoperability between the layers, first when a message is posted from the User to the MHS and later when it is delivered from the MHS to the User.

The operational service has evolved, although core aspects of the service, such as mailbox addressing and message format style, remaining remarkably constant. The original distinction between the user level and transfer level remains, but with elaborations in each. The term "Internet Mail" is used to refer to the entire collection of user and transfer components and services.

For Internet Mail, the term "end-to-end" usually refers to a single posting and the set of deliveries that result from a single transit of the MHS. A common exception is group dialogue that is mediated, through a Mailing List; in this case, two postings occur before intended Recipients receive an Author's message, as discussed in Section 2.1.3. In fact, some uses of email consider the entire email service, including Author and Recipient, as a subordinate component. For these services, "end-to-end" refers to points outside the email service. Examples are voicemail over email "[RFC3801], EDI over email [RFC1767] and facsimile over email [RFC4142].

Figure 1: Basic Internet Mail Service Model

End-to-end Internet Mail exchange is accomplished by using a standardized infrastructure with these components and characteristics:

The end-to-end portion of the service is the email object, called a “message.” Broadly, the message itself distinguishes control information, for handling, from the Author's content.

A precept to the design of mail over the open Internet is permitting user-to-user and MTA-to-MTA interoperability without prior, direct arrangement between the independent administrative authorities responsible for handling a message. All participants rely on having the core services universally supported and accessible, either directly or through Gateways that act as translators between Internet Mail and email environments conforming to other standards. Given the importance of spontaneity and serendipity in interpersonal communications, not requiring such prearrangement between participants is a core benefit of Internet Mail and remains a core requirement for it.

Within localized networks at the edge of the public Internet, prior administrative arrangement often is required and can include access control, routing constraints, and configuration of the information query service. Although recipient authentication has usually been required for message access since the beginning of Internet Mail, in recent years it also has been required for message submission. In these cases, a server validates the client's identity, whether by explicit security protocols or by implicit infrastructure queries to identify "local" participants.

References to structured fields of a message use a two-part dotted notation. The first part cites the document that contains the specification for the field and the second is the name of the field. Hence <RFC2822.From> is the From: header field in an email content header and <RFC2821.MailFrom> is the address in the SMTP "Mail From" command.

When occurring without the RFC2822 qualifier, header field names are shown with a colon suffix. For example, From:.

References to labels for actors, functions or components have the first letter capitalized.

Also, the key words "MUST", "MUST NOT", "REQUIRED", "SHALL", "SHALL NOT", "SHOULD", "SHOULD NOT", "RECOMMENDED", "MAY", and "OPTIONAL" in this document are to be interpreted as described in RFC 2119 [RFC2119] [RFC2119].

Internet Mail is a highly distributed service, with a variety of actors playing different roles. These actors fall into three basic types:

Although related to a technical architecture, the focus on actors concerns participant responsibilities, rather than functionality of modules. For that reason, the labels used are different from those used in classic email architecture diagrams.

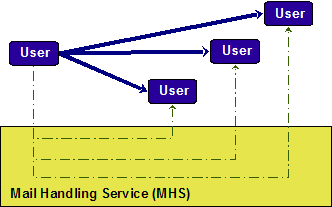

Users are the sources and sinks of messages. Users can be people, organizations, or processes. They can have an exchange that iterates, and they can expand or contract the set of users that participate in a set of exchanges. In Internet Mail, there are four types of Users:

Figure 2 shows the primary and secondary flows of messages among them.

Figure 2: Relationships Among User Actors

From the user perspective, all mail transfer activities are performed by a monolithic Mail Handling Service (MHS), even though the actual service can be provided by many independent organizations. Users are customers of this unified service.

Whenever any MHS actor sends information to back to an Author or Originator in the sequence of handling a message, that actor is a User.

The Author is responsible for creating the message, its contents, and its list of recipient addresses. The MHS transfers the message from the Author and delivers it to the Recipients. The MHS has an Originator role (Section 2.2.1) that correlates with the Author role.

The Recipient is a consumer of the delivered message. The MHS has a Receiver role (Section 2.2.4)correlates with the Recipient role. This is labeled Recv in Figure 3.

Any Recipient can close the user communication loop by creating and submitting a new message that replies to the Author. An example of an automated form of reply is the Message Disposition Notification (MDN), which informs the Author about the Recipient's handling of the message. (See Section 4.1.)

The Return Handler, also called "Bounce Handler," receives and services notifications that the MHS generates, as it transfers or delivers the message. These notices can be about failures or completions and are sent to an address that is specified by the Originator<<initial def>> . This Return handling address (also known as a Return address) might have no visible characteristics in common with the address of the Author or Originator.

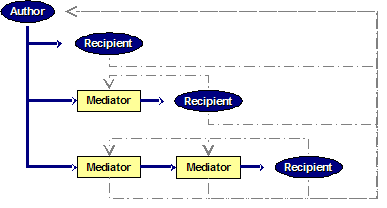

A Mediator receives, aggregates, reformulates, and redistributes messages among Authors and Recipients who are the principals in protracted exchanges. This activity is easily confused with the underlying MHS transfer exchanges. However, each serves very different purposes and operates in very different ways.

When mail is delivered to the Mediator specified in the RFC2821.RcptTo command, the MHS handles it the same way as for any other Recipient. The MHS sees each posting and delivery activity between sources and sinks as independent; it does not see subsequent re-posting as a continuation of a process. Because the Mediator originates messages, it can receive replies. Hence, when submitting messages, the Mediator is an Author. So a Mediator really is a full-fledged User. Mediators are considered extensively in Section 5.

The distinctive aspects of a Mediator are outside the MHS. A Mediator preserves the Author information of the message it reformulates and is permitted to make meaningful changes to the message content or envelope. The MHS sees a new message, but users receive a message that they interpret as being from, or at least initiated by, the Author of the original message. The role of a Mediator is not limited to merely connecting other participants; the Mediator is responsible for the new message.

A Mediator's role is complex and contingent, for example, modifying and adding content or regulating which users are allowed to participate and when. The common example of this role is a group Mailing List. In a more complex use, a sequence of Mediators could perform a sequence of formal steps, such as reviewing, modifying, and approving a purchase request.

A Gateway is a particularly interesting form of Mediator. It is a hybrid of User and Relay that connects heterogeneous mail services. Its purpose is to emulate a Relay. For a detailed discussion, see Section 2.2.3. .

The Mail Handling Service (MHS) performs a single end-to-end transfer on behalf of the Author to reach the Recipient addresses specified in the original RFC2821.RcptTo commands. Exchanges that are either mediated or iterative and protracted, such as those used for collaboration over time are handled by the User actors, not by the MHS actors.

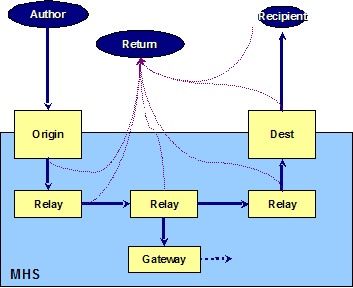

Figure 3 shows the relationships among transfer participants in Internet Mail. Although it shows the Originator (labeled Origin) as distinct from the Author and Receiver (labeled Recv) as distinct from Recipient, each pair of roles usually has the same actor. Transfers typically entail one or more Relays. However direct delivery from the Originator to Receiver is possible. Intra-organization mail services usually have only one Relay.

Figure 3: Relationships Among MHS Actors

The Originator ensures that a message is valid for posting and then submits it to a Relay. A message is valid if it conforms to both Internet Mail standards and local operational policies. The Originator can simply review the message for conformance and reject it if it finds errors, or it can create some or all of the necessary information. In effect, the Originator is responsible for the functions of the Mail Submission Agent.

The Originator operates with dual allegiance. It serves the Author and can be the same entity. But its role in assuring validity means that it MUST also represent the local operator of the MHS, that is, the local ADministrative Management Domain (ADMD).

The Originator also performs any post-submission, Author-related administrative tasks associated with message transfer and delivery. Notably, these tasks pertain to sending error and delivery notices, enforcing local policies, and dealing with messages from the Author that prove to be problematic for the Internet. The Originator is accountable for the message content, even when it is not responsible for it. The Author creates the message, but the Originator handles any transmission issues with it.

The Relay performs MHS-level transfer-service routing and store-and-forward, by transmitting or retransmitting the message to its Recipients. The Relay adds trace information [RFC2505] but does not modify the envelope information or the message content semantics. It can modify message content representation, such as changing the form of transfer encoding from binary to text, but only as required to meet the capabilities of the next hop in the MHS.

A Mail Handling Service (MHS) network consists of a set of Relays. This network is above any underlying packet-switching network that might be used and below any Gateways or other Mediators.

In other words, email scenarios can involve three distinct architectural layers, each providing its own type of data of store-and-forward service:

The bottom layer is the Internet's IP service. The most basic email scenarios involve Relays and Switches.

Aborting a message transfer makes the Relay an Author because it must send an error message to the Return address. The potential for looping is avoided by omitting a Return address from this message.

A Gateway is a hybrid of User and Relay that connects heterogeneous mail services. Its purpose is to emulate a Relay and the closer it comes to this, the better. A Gateway operates as a User when it needs the ability to modify message content.

Differences between mail services can be as small as minor syntax variations, but they usually encompass significant, semantic distinctions. One difference could be email addresses that are hierarchical and machine-specific rather than a flat, global namespace. Another difference could be support for text-only content or multi-media. Hence the Relay function in a Gateway presents a significant design challenge, if the resulting performance is to be seen as nearly seamless. The challenge is to ensure user-to-user functionality between the services, despite differences in their syntax and semantics.

The basic test of Gateway design is whether an Author on one side of a Gateway can send a useful message to a Recipient on the other side, without requiring changes to any components in the Author's or Recipient's mail services other than adding the Gateway. To each of these otherwise independent services, the Gateway appears to be a native participant. But the ultimate test of Gateway design is whether the Author and Recipient can sustain a dialogue. In particular, can a Recipient's MUA automatically formulate a valid Reply that will reach the Author?

The Receiver performs final delivery or sends the message to an alternate address. It can also perform filtering and other policy enforcement immediately before or after delivery.

Administrative actors can be associated with different organizations, each with its own administrative authority. This operational independence, coupled with the need for interaction between groups, provides the motivation to distinguish among ADministrative Management Domains (ADMDs ). Each ADMD can have vastly different operating policies and trust-based decision-making. One obvious example is the distinction between mail that is exchanged within an organization and mail that is exchanged between independent organizations. The rules for handling both types of traffic tend to be quite different. That difference requires defining the boundaries of each, and this requires the ADMD construct.

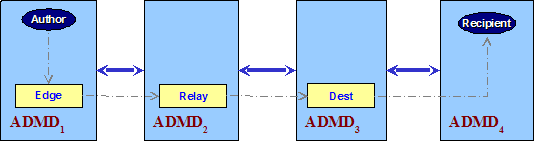

Operation of Internet Mail services is carried out by different providers (or operators). Each can be an independent ADMD. This independence of administrative decision-making defines boundaries that distinguish different portions of the Internet Mail service. A department that operates a local Relay, an IT department that operates an enterprise Relay, and an ISP that operates a public shared email service can be configured into many combinations of administrative and operational relationships. Each is a distinct ADMD, potentially having a complex arrangement of functional components. Figure 4 depicts relationships among ADMDs. The benefit of the ADMD construct is to facilitate discussion about designs, policies and operations that need to distinguish between internal issues and external ones.

The architectural impact of the need for boundaries between ADMDs is discussed in [Tussle]. Most significant is that the entities communicating across ADMD boundaries typically have the added burden of enforcing organizational policies concerning external communications. At a more mundane level, routing mail between ADMDs can be an issue, such as needing to route mail for partners over specially trusted paths.

These are the basic types of ADMDs:

The mail-level transit service is different from packet-level switching. End-to-end packet transfers usually go through intermediate routers; email exchange across the open Internet can be directly between the Boundary MTAs of Edge ADMDs. This distinction between direct and indirect interaction highlights the differences discussed in Section 2.2.2

Figure 4: Administrative Domain (ADMD) Example

Edge networks can use proprietary email standards internally. However the distinction between Transit network and Edge network transfer services is significant because it highlights the need for concern over interaction and protection between independent administrations. In particular, this distinction calls for additional care in assessing the transitions of responsibility and the accountability and authorization relationships among participants in message transfer.

The interactions of ADMD components are subject to the policies of that domain, which cover concerns such as these:

These policies can be implemented in different functional components, according to the needs of the ADMD. For example, see [RFC5068].

Consumer, Edge, and Transit services can be offered by providers that operate component services or sets of services. Further, it is possible for one ADMD to host services for other ADMDs.

These are common examples of ADMDs:

Practical operational concerns demand that providers be involved in administration and enforcement issues. This involvement can extend to operators of lower-level packet services.

Internet Mail uses three forms of identity: mailbox, domain name, and message-ID. Each must be globally unique.

A mailbox is specified as an Internet Mail address <addr‑spec>. It has two distinct parts, separated by an at‑sign (@). The right side is a globally interpreted domain name associated with an ADMD. Domain names are discussed in Section 3.3. Formal Internet Mail addressing syntax can support source routes, to indicate the path through which a message ought to be sent. The use of source routes is not common and has been deprecated in [RFC2821].

The portion to the left of the at‑sign contains a string that is globally opaque and is called the <local‑part>. It is to be interpreted only by the entity specified by the address's domain name. Except as noted later in this section all other entities MUST treat the <local‑part> as an uninterpreted literal string and MUST preserve all of its original details. As such its public distribution is equivalent to sending a Web browser "cookie" that is only interpreted upon being returned to its creator.

Some local‑part values have been standardized, for contacting personnel at an organization. These names cover common operations and business functions. [RFC2142]

It is common for sites to have local structuring conventions for the left-hand side <local‑part> of an <addr‑spec>. This permits sub-addressing, such as for distinguishing different discussion groups used by the same participant. However it is worth stressing that these conventions are strictly private to the user's organization and MUST NOT be interpreted by any domain except the one listed in the right side of the <addr‑spec>. The exceptions are those specialized services that conform to public, standardized conventions, as noted below.

A few types of addresses elaborate on basic email addressing, with a standardized, global schema for the <local‑part>, Include are conventions between authoring systems and Gateways. They are invisible to the public email transfer infrastructure. When an Author is explicitly sending through a Gateway out of the Internet, coding conventions for the <local‑part> allow the Author to formulate instructions for the Gateway. Standardized examples of such conventions are the telephone numbering formats for VPIM [RFC3801], such as:

+16137637582@vpim.example.com

and iFax [RFC3192], such as:

FAX=+12027653000/T33S=1387@ifax.example.com

Email addresses are being used far beyond their original role in email transfer and delivery. In practical terms, an email address string has become the common identifier for representing online identity. Hence, it is essential to be clear about both the nature and role of an identity string in a particular context and the entity responsible for setting that string. For example, see Section 4.1.4, Section 4.3.3 and Section 5.

A domain name is a global reference to an Internet resource, such as a host, a service, or a network. A domain name usually maps to one or more IP Addresses. Conceptually, the name can encompass an organization, a collection of machines integrated into a homogeneous service, or a single machine. A domain name can be administered to refer to individual users, but this is not common practice. The name is structured as a hierarchical sequence of names, separated by dots (.), with the top of the hierarchy being on the right end of the sequence. Domain names are defined and operated through the Domain Name System (DNS) [RFC1034], [RFC1035], [RFC2181].

When not part of a mailbox address, a domain name is used in Internet Mail to refer to the ADMD or to the host that took action upon the message, such as providing the administrative scope for a message identifier or performing transfer processing.

There are two standardized tags for identifying messages: Message-ID: and ENVID. A Message-ID: pertains to content, and an ENVID pertains to transfer.

Internet Mail standards provide for, at most, a single Message-ID:. The Message-ID: for a single message, which is a user-level tag, has a variety of uses including threading, aiding identification of duplicates, and DSN tracking. [RFC2822]. The Originator assigns the Message-ID:. The Recipient's ADMD is the intended consumer of the Message-ID:, although any actor along the transfer path can use it.

Message-ID: MUST be globally unique. Its format is similar to that of a mailbox, with two distinct parts, separated by an at‑sign (@). Typically, the right side specifies the ADMD or host that assigns the identifier, and the left side contains a string that is globally opaque and serves to uniquely identify the message within the domain referenced on the right side. The duration of uniqueness for the message identifier is undefined.

When a message is revised in any way, the decision whether to assign a new Message-ID: requires a subjective assessment to determine whether the editorial content has been changed enough to constitute a new message. [RFC2822] states that "a message identifier pertains to exactly one instantiation of a particular message; subsequent revisions to the message each receive new message identifiers." Yet experience suggests that some flexibility is needed. An impossible test is whether the recipient will consider the new message to be equivalent to the old one. For most components of Internet Mail, there is no way to predict a specific recipient's preferences on this matter. Both creating and failing to create a new Message-ID: have their downsides.

Here are some guidelines and examples:

The absence of both objective, precise criteria for re-generating a Message-ID: and strong protection associated with the string means that the presence of an ID can permit an assessment that is marginally better than a heuristic, but the ID certainly has no value on its own for strict formal reference or comparison. For that reason, the Message-ID: SHOULD NOT be used for any function that has security implications.

The ENVID (envelope identifier) can be used for message-tracking purposes [RFC3885] concerning a single posting/delivery transfer. The ENVID labels a single transit of the MHS by a specific message. So, the ENVID is used for one message posting, until that message is delivered. A re-posting of the message, such as by a Mediator, does not re-use that ENVID, but can use a new one, even though the message might legitimately retain its original Message-ID:.

The format of an ENVID is free form. Although its creator might choose to impose structure on the string, none is imposed by Internet standards. By implication, the scope of the string is defined by the domain name of the Return Address.

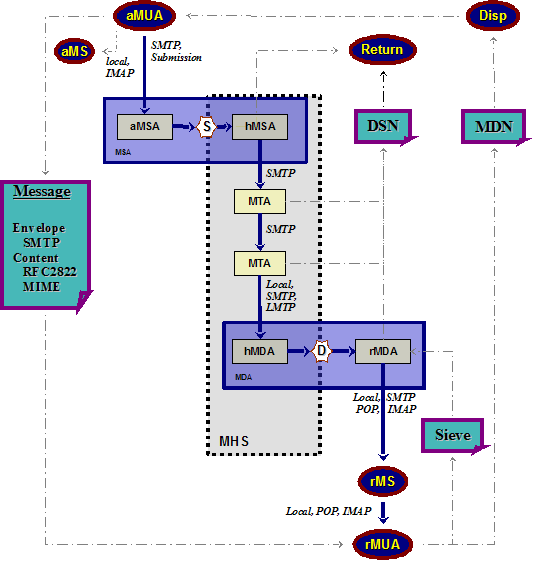

The Internet Mail architecture comprises six basic types of functionality, which are arranged to support a store-and-forward service. As shown in Figure 5, each type can have multiple instances, some of which represent specialized roles. This section considers the activities and relationships among these components, and the Internet Mail standards that apply to them.

This figure shows function modules and the standardized protocols used between them.

Figure 5: Protocols and Services

The purpose of the Mail Handling Service (MHS) is to exchange a message object among participants [RFC2822], [RFC0822]. All of its underlying mechanisms serve to deliver that message from its Author to its Recipients. A message can be explicitly labeled as to its nature [RFC3458].

A message comprises a transit-handling envelope and the message content. The envelope contains information used by the MHS. The content is divided into a structured header and the body. The header comprises transit handling trace information and structured fields that are part of the Author’s message content. The body can be unstructured lines of text or a tree of multi-media subordinate objects, called “body-parts” or attachments [RFC2045], [RFC2046], [RFC2047], [RFC4288], [RFC4289], [RFC2049].

In addition, Internet Mail has a few conventions for special control data, notably:

Internet Mail has a fragmented framework for transit-related handling information. Information that is used directly by the MHS is called the "envelope." It directs handling activities by the transfer service and is carried in transfer service commands. That is, the envelope exists in the transfer protocol SMTP. [RFC2821]

Trace information, such as RFC2822.Received, is recorded in the message header and is not subsequently altered. [RFC2822]

Header fields are attribute name/value pairs that cover an extensible range of email service parameters, structured user content, and user transaction meta-information. The core set of header fields is defined in [RFC2822], [RFC0822]. It is common practice to extend this set for different applications. Procedures for registering header fields are defined in [RFC3864]. An extensive set of existing header field registrations is provided in [RFC4021].

One danger of placing additional information in header fields is that Gateways often alter or delete them.

The body of a message might be lines of ASCII text or a hierarchically structured composition of multi-media body-part attachments, using MIME. [RFC2045], [RFC2046], [RFC2047], [RFC4288], [RFC2049]

Table 1 lists the core identifiers present in a message during transit.

| Layer | Field | Set By |

|---|---|---|

| Message Body | MIME Header | Author |

| Message header fields | From: | Author |

| Sender: | Originator | |

| Reply-To: | Author | |

| To:, CC:, BCC: | Author | |

| Message-ID: | Originator | |

| Received: | Originator, Relay, Receiver | |

| Return-Path: | MDA, from MailFrom | |

| Resent-*: | Mediator | |

| List-Id: | Mediator | |

| List-*: | Mediator | |

| SMTP | HELO/EHLO | Latest Relay Client |

| ENVID | Originator | |

| MailFrom | Originator | |

| RcptTo | Author | |

| ORCPT | Author | |

| IP | Source Address | Latest Relay Client |

Table 1: Layered Identities

These are the most common address-related fields:

Interactions at the user level entail protocol exchanges, distinct from those that occur at lower layers of the Internet Mail MHS architecture that is, in turn, above the Internet Transport layer. Because the motivation for email, and much of its use, is for interaction among people, the nature and details of these protocol exchanges often are determined by the needs of interpersonal and group communication. To accommodate the idiosyncratic behavior inherent in such communication, only subjective guidelines, rather than strict rules, can be offered for some aspects of system behavior. Mailing Lists provide particularly salient examples.

A Mail User Agent (MUA) works on behalf of User actors and User applications. It is their representative within the email service.

The Author MUA (aMUA) creates a message and performs initial submission into the transfer infrastructure via a Mail Submission Agent (MSA). It can also perform any creation- and posting-time archival in its Message Store (aMS). An MUA aMS can organize messages in many different ways. A common model uses aggregations, called "folders". This model allows a folder for messages under development (Drafts), a folder for messages waiting to be sent (Queued or Unsent), and a folder for messages that have been successfully posted for transfer (Sent). But none of these folders is required. For example, IMAP allows drafts to be stored in any folder; so no Drafts folder is present.

The Recipient MUA (rMUA) works on behalf of the Recipient to process received mail. This processing includes generating user-level disposition control messages, displaying and disposing of the received message, and closing or expanding the user communication loop by initiating replies and forwarding new messages.

A Mediator is special class of MUA. It performs message re-posting, as discussed in Section 2.1.

An MUA can be automated, on behalf of a user who is not present at the time the MUA is active. One example is a bulk sending service that has a timed-initiation feature. These services are not to be confused with a mailing list Mediator, since there is no incoming message triggering the activity of the automated service.

A popular and problematic MUA is an automatic responder, such as one that sends out-of-office notices. This behavior might be confused with that of a Mediator, but this MUA is generating a new message. Automatic responders can annoy users of mailing lists unless they follow [RFC3834]. ****** The recommendations in RFC 3834 are an important consequence of the addressing architecture of Internet Mail so they do help illustrate the architecture. *****

These identity fields are relevant to a typical MUA:

An MUA can employ a long-term Message Store (MS). Figure 5 depicts an Author’s MS (aMS) and a Recipient’s MS (rMS). An MS can be located on a remote server or on the same machine as the MUA.

An MS acquires messages from an MDA either by a local mechanism or by using POP or IMAP. The MUA accesses the MS either by a local mechanism or by using POP or IMAP. Using POP for message access, rather than bulk transfer, is rare, awkward, and largely non-standard.

A Mail Submission Agent (MSA) accepts the message submitted by the aMUA and enforces the policies of the hosting ADMD and the requirements of Internet standards. An MSA represents an unusual functional dichotomy. It represents the interests of the Author (aMUA) during message posting, to facilitate posting success; it also represents the interests of the MHS. In the architecture, these responsibilities are modeled, as shown in Figure 5, by dividing the MSA into two sub-components, aMSA and hMSA, respectively. Transfer of responsibility for a single message, from an Author's environment to the MHS, is called "posting". In Figure 5 it is marked as the (S) transition, within the MSA.

The hMSA takes transit responsibility for a message that conforms to the relevant Internet standards and to local site policies. It rejects messages that are not in conformance. The MSA performs final message preparation for submission and effects the transfer of responsibility to the MHS, via the hMSA. The amount of preparation depends upon the local implementations. Examples of oMSA tasks include adding header fields, such as Date: and Message-ID:, and modifying portions of the message from local notations to Internet standards, such as expanding an address to its formal RFC2822 representation.

Historically, standards-based MUA/MSA message postings have used SMTP. [RFC2821] The standard currently preferred is SUBMISSION. [RFC4409] Although SUBMISSION derives from SMTP, it uses a separate TCP port and imposes distinct requirements, such as access authorization.

These identities are relevant to the MSA:

A Mail Transfer Agent (MTA) relays mail for one application-level "hop." It is like a packet-switch or IP router in that its job is to make routing assessments and to move the message closer to the Recipients. Of course, email objects are typically much larger than the payload of a packet or datagram, and the end-to-end latencies are typically much higher. Relaying is performed by a sequence of MTAs, until the message reaches a destination MDA. Hence, an MTA implements both client and server MTA functionality; it does not change addresses in the envelope or reformulate the editorial content. A change in data form, such as to MIME Content-Transfer-Encoding, is within the purview of an MTA, but removal or replacement of body content is not. An MTA also adds trace information. [RFC2505]

Internet Mail uses SMTP [RFC2821], [RFC0821] primarily to effect point-to-point transfers between peer MTAs. Other transfer mechanisms include Batch SMTP [RFC2442] and ODMR [RFC2645]. As with most network layer mechanisms, the Internet Mail SMTP supports a basic level of reliability, by virtue of providing for retransmission after a temporary transfer failure. Unlike typical packet switches (and Instant Messaging services), Internet Mail MTAs are expected to store messages in a manner that allows recovery across service interruptions, such as host system shutdown. The degree of such robustness and persistence by an MTA can vary. The base SMTP specification provides a framework for protocol response codes. An extensible enhancement to this framework is defined in [RFC5248]

The primary routing mechanism for Internet Mail is the DNS MX record [RFC1035], which specifies an MTA through which the queried domain can be reached. This mechanism presumes a public, or at least a common, backbone that permits any attached MTA to connect to any other.

MTAs can perform any of these well-established roles:

These identities are relevant to the MTA:

A transfer of responsibility from the MHS to a Recipient's environment (mailbox) is called "delivery." In the architecture, as depicted in Figure 5, delivery takes place within a Mail Delivery Agent (MDA) and is shown as the (D) transition from the MHS-oriented MDA component (hMDA) to the Recipient-oriented MDA component (rMDA).

An MDA can provide distinctive, address-based functionality, made possible by its detailed information about the properties of the destination address. This information might also be present elsewhere in the Recipient's ADMD, such as at an organizational border (Boundary) Relay. However, it is required for the MDA, if only because the MDA is required to know where to deliver the message.

Like an MSA, an MDA serves two roles, as depicted in Figure 5. Formal transfer of responsibility, called "delivery", is effected between the two components that embody these roles as shows as "(D)" in Figure 5. The MHS portion (hMDA) primarily functions as a server SMTP engine. A common additional role is to re-direct the message to an alternative address, as specified by the recipient addressee's preferences. The job of the recipient portion of the MDA (rMDA) is to perform any delivery actions that the Recipient specifies.

Transfer into the MDA is accomplished by a normal MTA transfer mechanism. Transfer from an MDA to an MS uses an access protocol, such as POP or IMAP.

These identities are relevant to the MDA:

From the origination site to the point of delivery, Internet Mail usually follows a "push" model. That is, the actor that holds the message initiates transfer to the next venue, typically with SMTP [RFC2821] or LMTP [RFC2033]. With a "pull" model, the actor that holds the message waits for the actor in the next venue to initiate a request for transfer. Standardized mechanisms for pull-based MHS transfer are ETRN [RFC1985] and ODMR [RFC2645].

After delivery, the Recipient's MUA (or MS) can gain access by having the message pushed to it or by having the receiver of access pull the message, such as by using POP [RFC1939] and IMAP [RFC3501].

A discussion of any interesting system architecture often bogs down when architecture and implementation are confused. An architecture defines the conceptual functions of a service, divided into discrete conceptual modules. An implementation of that architecture can combine or separate architectural components, as needed for a particular operational environment. For example, a software system that primarily performs message relaying is an MTA, yet it might also include MDA functionality. That same MTA system might be able to interface with non-Internet email services and thus perform both as an MTA and as a Gateway.

Similarly, implemented modules might be configured to form elaborations of the architecture. An interesting example is a distributed MS. One portion might be a remote server and another might be local to the MUA. As discussed in [RFC1733], there are three operational relationships among such MSs:

Basic message transfer from Author to Recipients is accomplished by using an asynchronous store-and-forward communication infrastructure in a sequence of independent transmissions through some number of MTAs. A very different task is a sequence of postings and deliveries through Mediators. A Mediator forwards a message, through a re-posting process. The Mediator shares some functionality with basic MTA relaying, but has greater flexibility in both addressing and content than is available to MTAs.

This is the core set of message information that is commonly set by all types of Mediators:

The aspect of a Mediator that distinguishes it from any other MUA creating a message is that a Mediator preserves the integrity and tone of the original message, including the essential aspects of its origination information. The Mediator might also add commentary.

Examples of MUA messages that a Mediator does not create include:

The remainder of this section describes common examples of Mediators.

One function of an MDA is to determine the internal location of a mailbox in order to perform delivery. An Alias is a simple re-addressing facility that provides one or more new Internet Mail addresses, rather than a single, internal one; the message continues through the transfer service, for delivery to one or more alternate addresses. Although typically implemented as part of an MDA, this facility is a Recipient function. It resubmits the message, although all handling information except the envelope recipient (rfc2821.RcptTo) address is retained. In particular, the Return address (rfc2821.MailFrom) is unchanged.

What is distinctive about this forwarding mechanism is how closely it resembles normal MTA store-and-forward relaying. Its only significant difference is that it changes the RFC2821.RcptTo value. Because this change is so small, aliasing can be viewed as a part of the lower-level mail relaying activity. However, this small change has a large semantic impact: The designated recipient has chosen a new recipient.

Alias typically changes only envelope information:

Also called the ReDirector, the ReSender's actions differ from forwarding because the Mediator "splices" a message's addressing information to connect the Author of the original message with the Recipient of the new message. This connection permits them to have direct exchange, using their normal MUA Reply functions, while also recording full reference information about the Recipient who served as a Mediator. Hence, the new Recipient sees the message as being from the original Author, even if the Mediator adds commentary.

These identities are relevant to a resent message:

A Mailing List receives messages as an explicit addressee and then re-posts them to a list of subscribed members. The Mailing List performs a task that can be viewed as an elaboration of the ReSender. In addition to sending the new message to a potentially large number of new Recipients, the Mailing List can modify content, for example, by deleting attachments, converting the format, and adding list-specific comments. Mailing Lists also archive messages posted by Authors. Still the message retains characteristics of being from the original Author.

These identities are relevant to a mailing list processor, when submitting a message:

A Gateway performs the basic routing and transfer work of message relaying, but it also is permitted to modify content, structure, address, or attributes as needed to send the message into a messaging environment that operates under different standards or potentially incompatible policies. When a Gateway connects two differing messaging services, its role is easy to identify and understand. When it connects environments that follow similar technical standards, but significantly different administrative policies, it is easy to view a Gateway as merely an MTA.

The critical distinction between an MTA and a Gateway is that a Gateway can make substantive changes to a message to map between the standards. In virtually all cases, this mapping results in some degree of semantic loss. The challenge of Gateway design is to minimize this loss. Standardized gateways to Internet Mail are facsimile [RFC4143], voicemail [RFC3801], and MMS [RFC4356]

A Gateway can set any identity field available to an MUA. These identities are typically relevant to Gateways:

To enforce security boundaries, organizations can subject messages to analysis, for conformance with its safety policies. An example is detection of content classed as spam or a virus. A filter might alter the content, to render it safe, such as by removing content deemed unacceptable. Typically, these actions add content to the message that records the actions.

This document describes the existing Internet Mail architecture. It introduces no new capabilities. The security considerations of this deployed architecture are documented extensively in the technical specifications referenced by this document. These specifications cover classic security topics, such as authentication and privacy. For example, email transfer protocols can use standardized mechanisms for operation over authenticated and/or encrypted links, and message content has similar protection standards available. Examples of such mechanisms include SMTP-TLS [RFC3207], SMTP-Auth [RFC2554], OpenPGP [RFC4880], and S/MIME [RFC3851].

The core of the Internet Mail architecture does not impose any security requirements or functions on the end-to-end or hop-by-hop components. For example, it does not require participant authentication and does not attempt to prevent data disclosure.

Particular message attributes might expose specific security considerations. For example, the blind carbon copy feature of the architecture invites disclosure concerns, as discussed in section 7.2 of [RFC2821] and section 5 of [RFC2822]. Transport of text or non-text content in this architecture has security considerations that are discussed in [RFC2822], [RFC2045], [RFC2046], and [RFC4288] as well as the security considerations present in the IANA media types registry for the respective types.

Agents that automatically respond to email raise significant security considerations, as discussed in [RFC3834]. Gateway behaviors affect end-to-end security services, as discussed in [RFC2480]. Security considerations for boundary filters are discussed in [RFC5228].

See section 7.1 of [RFC2821] for a discussion of the topic of origination validation. As mentioned in Section 4.1.4, it is common practice for components of this architecture to use the [RFC0791].SourceAddr to make policy decisions [RFC2505], although the address can be "spoofed". It is possible to use it without authorization. SMTP and Submission authentication [RFC2554], [RFC4409] provide more secure alternatives.

The discussion of trust boundaries, ADMDs, actors, roles, and responsibilities in this document highlights the relevance and potential complexity of security factors for operation of an Internet mail service. The core design of Internet Mail to encourage open and casual exchange of messages has met with scaling challenges, as the population of email participants has grown to include those with problematic practices. For example, spam, as defined in [RFC2505], is a by-product of this architecture. A number of standards track or BCP documents on the subject have been issued. [RFC2505], [RFC5068], [RFC3685]

This document has no actions for IANA.

Because its origins date back to the use of ASCII, Internet Mail has had an ongoing challenge to support the wide range of necessary international data representations. For a discussion of this topic, see [MAIL-I18N].

| [MAIL-I18N] | Internet Mail Consortium, “Using International Characters in Internet Mail”, IMC IMCR-010, August 1998. |

| [RFC0821] | Postel, J.B., “Simple Mail Transfer Protocol”, STD 10, RFC 821, August 1982. |

| [RFC0822] | Crocker, D.H., “Standard for the format of ARPA Internet text messages”, STD 11, RFC 822, August 1982. |

| [RFC1733] | Crispin, M., “Distributed Electronic Models in IMAP4”, December 1994. |

| [RFC1767] | Crocker, D., “MIME Encapsulation of EDI Objects”, RFC 1767, March 1995. |

| [RFC1985] | De Winter, J., “SMTP Service Extension for Remote Message Queue Starting”, August 1996. |

| [RFC2033] | Myers, J.G., “Local Mail Transfer Protocol”, RFC 2033, October 1996. |

| [RFC2142] | Crocker, D., “Mailbox Names for Common services, Roles and Functions”, RFC 2142, May 1997. |

| [RFC2442] | “The Batch SMTP Media Type”, RFC 2442, November 1998. |

| [RFC2480] | Freed, N., “Gateways and MIME Security Multiparts”, RFC 2480, January 1999. |

| [RFC2505] | Lindberg, G., “Anti-Spam Recommendations for SMTP MTAs”, RFC 2505, February 1999. |

| [RFC2554] | Myers, J., “SMTP Service Extension for Authentication”, RFC 2554, March 1999. |

| [RFC3207] | Hoffman, P., “SMTP Service Extension for Secure SMTP over Transport Layer Security”, RFC 3207, February 2002. |

| [RFC3685] | Daboo, C., “SIEVE Email Filtering: Spamtest and VirusTest Extensions”, RFC 3685, February 2004. |

| [RFC3801] | Vaudreuil, G.M. and G.W. Parsons, “Voice Profile for Internet Mail - version 2 (VPIMv2)”, RFC 3801, June 2004. |

| [RFC3851] | Ramsdell, B., Ed., “Secure/Multipurpose Internet Mail Extensions (S/MIME) Version 3.1 Message Specification ”, RFC 3851, July 2004. |

| [RFC3885] | Allman, E. and T. Hansen, “SMTP Service Extension for Message Tracking”, RFC 3885, September 2004. |

| [RFC4142] | Crocker, D. and G. Klyne, “Full-mode Fax Profile for Internet Mail: FFPIM”, December 2005. |

| [RFC4143] | Toyoda, K. and D. Crocker, “Facsimile Using Internet Mail (IFAX) Service of ENUM”, RFC 4143, November 2005. |

| [RFC4356] | Gellens, R., “Mapping Between the Multimedia Messaging Service (MMS) and Internet Mail”, RFC 4356, January 2006. |

| [RFC4880] | Callas, J., Donnerhacke, L., Finney, H., Shaw, D., and R. Thayer, “OpenPGP Message Format”, RFC 4880, November 2007. |

| [RFC5068] | Hutzler, C., Crocker, D., Resnick, P., Sanderson, R., and E. Allman, “Email Submission Operations: Access and Accountability Requirements”, RFC 5068, BCP 134, Nov 2007. |

| [Tussle] | Clark, D., Wroclawski, J., Sollins, K., and R. Braden, “Tussle in Cyberspace: Defining Tomorrow’s Internet”, ACM SIGCOMM, 2002. |

This work derives from a section in an early version of [RFC5068]. Discussion of the Originator actor role was greatly clarified during discussions in the IETF's Marid working group.

Graham Klyne, Pete Resnick and Steve Atkins provided thoughtful insight on the framework and details of the original drafts, as did Chris Newman for the final versions, while also serving as cognizant Area Director for the document. Tony Hansen served as document shepherd, through the IETF process.

Later reviews and suggestions were provided by Eric Allman, Nathaniel Borenstein, Ed Bradford, Cyrus Daboo, Frank Ellermann, Tony Finch, Ned Freed, Eric Hall, Willemien Hoogendoorn, Brad Knowles, John Leslie, Bruce Valdis Kletnieks, Mark E. Mallett, David MacQuigg, Alexey Melnikov, der Mouse, S. Moonesamy, Daryl Odnert, Rahmat M. Samik-Ibrahim, Marshall Rose, Hector Santos, Jochen Topf, Greg Vaudreuil.

Diligent early proof-reading was performed by Bruce Lilly. Diligent technical editing was provided by Susan Hunziker

This document is subject to the rights, licenses and restrictions contained in BCP 78, and except as set forth therein, the authors retain all their rights.

This document and the information contained herein are provided on an “AS IS” basis and THE CONTRIBUTOR, THE ORGANIZATION HE/SHE REPRESENTS OR IS SPONSORED BY (IF ANY), THE INTERNET SOCIETY, THE IETF TRUST AND THE INTERNET ENGINEERING TASK FORCE DISCLAIM ALL WARRANTIES, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO ANY WARRANTY THAT THE USE OF THE INFORMATION HEREIN WILL NOT INFRINGE ANY RIGHTS OR ANY IMPLIED WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE.

The IETF takes no position regarding the validity or scope of any Intellectual Property Rights or other rights that might be claimed to pertain to the implementation or use of the technology described in this document or the extent to which any license under such rights might or might not be available; nor does it represent that it has made any independent effort to identify any such rights. Information on the procedures with respect to rights in RFC documents can be found in BCP 78 and BCP 79.

Copies of IPR disclosures made to the IETF Secretariat and any assurances of licenses to be made available, or the result of an attempt made to obtain a general license or permission for the use of such proprietary rights by implementers or users of this specification can be obtained from the IETF on-line IPR repository at <http://www.ietf.org/ipr>.

The IETF invites any interested party to bring to its attention any copyrights, patents or patent applications, or other proprietary rights that may cover technology that may be required to implement this standard. Please address the information to the IETF at ietf-ipr@ietf.org.